90% of tropical forests managed poorly or not at all

-----------------

MONGABAY.COM: 90% of tropical forests managed poorly or not at all

More than 90 percent of tropical forests are managed poorly or not at all, says a new assessment by the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO).

|

Graph (C) by Mongabay, 2011 |

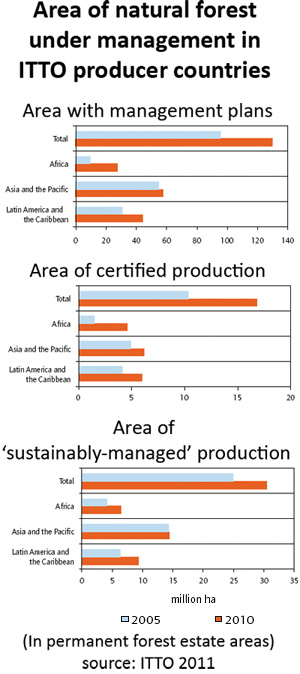

The report, Status of Tropical Forest Management 2011, finds that while forests continue to be degraded and destroyed at a rapid pace there are signs of hope. ITTO says the area of natural tropical forest under "sustainable management" in Africa, Asia-Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean increased by 47 percent from 36 million hectares (89 million acres) to 53 million hectares (134 million acres) between 2005 and 2010. Over the same time the extent of timber production under some form of management plan increased by about a third to 131 million hectares.

“We are of course happy to see the progress that has occurred in the last five years, but it still represents an incremental advance, and some countries are still lagging behind,” said Emmanuel Ze Meka, ITTO’s Executive Director, in a statement.

Graph (C) by Mongabay, 2011 |

The report, which collected detailed country-by-country data on forest management in the world’s major tropical timber producing countries, finds the most rapid gains in Africa, where forest areas with management plans increased 180 percent from 10 million hectares to 28 million hectares between 2005 and 2010. Latin America and the Caribbean saw its forest area under management plans increase 43 percent, while Asia's extent of forest management largely stagnated.

The report also reviews a number of the trends in forest management, including certification of timber products like that operated by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC); emerging payments for ecosystem services mechanisms like the much-hyped Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD) program, which aims to pay tropical countries for protecting their forests; and new regulations for timber imports like the Lacey Act.

The report concludes that each of these trends on its own probably won't be enough to ensure effective management of forests.

“We fully support the emergence of new markets for ‘green’ timber and the recent push to include forests in a climate change accord, but in many countries these developments alone may not be transformational," Meka said. "Demand for certified wood is likely to affect only a small part of the tropical forest estate."

Duncan Poore, an author of the report and former Director of the Nature Conservancy in the UK and former Director-General of the IUCN, said the REDD alone wouldn't provide enough of a financial incentive to keep forests standing in some countries. Therefore, he says, the move to expand the program to include "sustainable forest management" was "essential."

"With the economics of land-use in the tropics skewed away from maintaining forests for any purpose—either conservation or production—we need to ensure that we use all available tools that provide revenue for maintaining standing forests to compete with alternative land-uses such as agriculture and biofuels," he said in a statement. "REDD has considerable promise but it's essential that it evolves to recognize and support initiatives focusing on sustainable utilization of tropical forest resources, including sustainable timber production, as opposed to becoming primarily a fund to conserve forests."

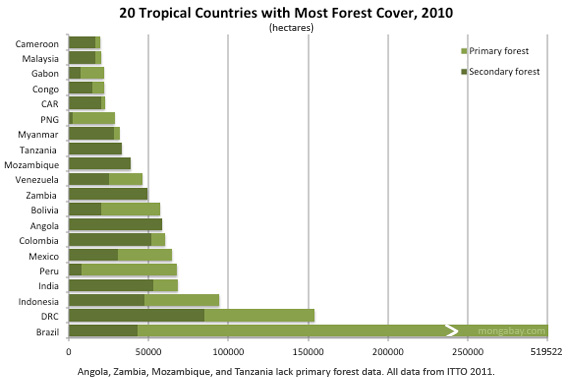

The inclusion of selective logging in REDD allows loggers to harvest virgin forests for timber. Accordingly, the report provides data on primary forest cover in many tropical countries. It also offers figures on deforestation rates since 2005, timber production, and allocation of forest lands as well as profiles for 33 tropical countries.

The report says resolving unclear land rights is critical to progress on forest management. Africa lags far behind other regions in sorting out land tenure; Latin America #8212; especially Brazil and Ecuador — has seen the most progress in addressing land title issues.

"Slowing or halting the loss or degradation of tropical forest will require disentangling the knot of tenure claims to many forested areas that is thwarting efforts to implement sustainable forestry," said Meka. "Sustainable forest management is unlikely to succeed unless the forest has secure tenure that has been determined transparently on the basis of negotiation between claimants."

The report notes that local communities need more resources to implement management programs, a position supported by Rights and Resources Initiative Coordinator Andy White, who was not involved in the publication.

“Today's report shows that less than 10 percent of all forests are sustainably managed and that ITTO expects deforestation to continue,” said Andy White, Coordinator of the Rights and Resources Initiative, in a statement. “The report also shows that reforming tenure and supporting community forestry are needed to prevent the continued loss of tropical forests and the industrial clearing and logging that leads to deforestation, poverty, and human rights abuses.”

“Today's report shows that less than 10 percent of all forests are sustainably managed and that ITTO expects deforestation to continue,” said Andy White, Coordinator of the Rights and Resources Initiative, in a statement. “The report also shows that reforming tenure and supporting community forestry are needed to prevent the continued loss of tropical forests and the industrial clearing and logging that leads to deforestation, poverty, and human rights abuses.”

CITATION: Blaser, J., Sarre, A., Poore, D. & Johnson, S. (2011). Status of Tropical Forest Management 2011. ITTO Technical Series No 38. International Tropical Timber Organization, Yokohama, Japan.

NATURE.COM: Sustainable management of tropical forests has a long way to go

Less than 10% of permanent tropical forests are under a sustainable management plan, according to a study by the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO) an intergovernmental organization based in Yokohama, Japan, whose 33 timber-producing members account for around 85% of the world's tropical forests.

Between 2005 and 2010, the amount of land in the tropics designated as "permanently forested" — which must legally remain forested rather than be converted to agriculture or other land uses — and under sustainable management grew from around 36 million hectares to around 53 million hectares, an increase of nearly 50%. But this still represents only 7% of the 761 million hectares of the permanent forest estate in ITTO member countries and only 3% of tropical forests globally.

Duncan Poore, a former director-general of the World Conservation Union and a co-author of the ITTO report, says the figures point to a step in the right direction. "In the mid-1980s, probably less than a million hectares of tropical forest were being managed sustainably," says Poore, who helped the ITTO put together its first forest-status compilation in 1987.

Since the ITTO's last report in 2005, though, countries such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia and Nigeria have stumbled with their forestry targets because of war or lack of resources. But other countries, such as Brazil, Gabon and Malaysia, have made real progress towards sustainable forest management, according to the report.

Changing the conservation paradigm

The report moves beyond timber production to discuss ways of reducing deforestation through financial mechanisms such as UN REDD programme (reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation) — the idea of paying poor countries to preserve their forests rather than cut them down. It also warns that rising food and fuel prices could easily favour the conversion of land for agriculture and other uses over forest conservation.

Doug Boucher, head of the Tropical Forest and Climate Initiative at the Union of Concerned Scientists, a non-profit organization based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, says on a whole this shows that the ITTO is moving away from the "old-fashioned mindset" that timber production in permanent forest estates under a sustainable management plan at a profit could rescue tropical forests.

"Little by little the ITTO are starting to realize that it's just not working and they have to adapt to the new realities of the twenty-first century," says Boucher.

In Ivory Coast, for example, the permanent forest estate is recorded as 4.2 million hectares, but only 1.95 million of those are still forested. "The permanent forest estate is not a permanent solution and it is not real," says Boucher. "If something is legally a permanent forest but in reality it is not, how can you trust the data on the permanent forest estate as being anything real?"

Numbers count

The main achievement of the report is that it is "enormously comprehensive", says Poore. "It is much better than in 2005, and it provides a baseline for measuring future improvement."

But although the 2011 data might be superior, having more and better data can be a problem from an analytical point of view, especially when comparing with the previous data, says Boucher. "Some changes may be real or simply appear because of better data. And if the previous data is not trustworthy, you can't say anything."

This is especially true in quantifying the permanent forest estate, he says. "A table shows a substantial decrease in protected area overall, and the ITTO argues that this is due to greater clarity in the data, rather than any change in the legal status of such areas. That may be true, but you can't tell from what they show," says Boucher. "And if they are going to dismiss a trend when it's negative, you have to ask why they don't dismiss some of the trends that seem positive."

"For Malaysia, the report reads like fiction," adds Sam Lawson, director of Earthsight, a London-based non-governmental organization that investigates environmental wrongdoings. Whereas the report suggests that Malaysia has made progress towards sustainable management, "[it] makes no mention of the fact that recent independent remote-sensing analysis suggests that the deforestation rate in Sarawak (Malaysia's largest state) is the worst in the world," he says. "I suspect that the coverage of other countries is equally inaccurate and misleading."

Poore agrees that despite improvements since the ITTO's last report in 2005, there are still some limitations to the data. "We have to treat these figures with caution, despite the fact that they are the best available," he says.

But, Poore adds, the development of REDD activities could be just the solution to close the gap on the numbers debate. "One of things that REDD does involve is monitoring, so one hopes that those countries that are engaged in the REDD process may be able to improve the quality of the information they provide."

BusinessGreen.com: Report: Tropical timber trade boosts sustainable management

Governments will today be called on to help fund tropical forested countries design and implement sustainable forest management plans, as a major new report highlights that despite increased global efforts, less than 10 per cent of land which countries plan to maintain as tropical forest is being managed sustainably.

The International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO) will today release what is being hailed as the largest and most comprehensive assessment of forest cover and management in the 33 countries that control more than 90 per cent of the tropical timber trade.

Speaking to BusinessGreen, professor Duncan Poore, one of the report's authors, said the study presents a mixed bag of results, showing an increased understanding among governments of the need for forest management, but also highlighting the urgent need for further action.

The study found that between 2005 and 2010, the area of natural forest under management plans in the 33 ITTO producer countries increased by 69 million hectares to 183 million hectares.

ITTO's 2010 research also received more responses than in 2005, with 32 of 33 governments filing reports last year, compared with 21 of 33 in 2005.

The report said that countries that made notable progress towards more sustainable forest management in the past five years include Brazil, Gabon, Guyana, Malaysia and Peru. However, it also noted that countries affected by war, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, had understandably failed to boost sustainable management of forests.

The report also notes that despite improvements in reporting, less than 10 per cent of the total tropical forest resource that countries plan to maintain as forest is being managed sustainably.

The report urges aid organisations to help fund ITTO producer countries to undertake detailed inventories of their PFE, particularly to help ensure the success of REDD+ schemes by providing reference-level data on forest extent and quality.

The study comes just days after a separate report from the UN Environment Programme, which concluded that an investment of $40bn a year could serve to halve global deforestation rates.

---------------