POST Copenhagen: the point of view of the EU

-----------------

Pablo Solón, Ambassador to the UN for the Plurinational State of Bolivia:

In the EU report called International climate policy post-Copenhagen (cited below as well), the commission confirmed that the pledges by developed countries are equal to between 13.2% and 17.8% in emissions reductions by 2020 – far below the required 40%-plus reductions needed to keep global temperature rise to less than 2C degrees.

The situation is even worse once you take into account what are called "banking of surplus emission budgets" and "accounting rules for land use, land use change and forestry". The Copenhagen accord would actually allow for an increase in developed country emissions of 2.6% above 1990 levels. This is hardly a forward step.

This is not just about gravely inadequate commitments, it is also about process. Whereas before, under the Kyoto protocol, developed countries were legally bound to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by a certain percentage, now countries can submit whatever targets they want without a binding commitment.

Read as well here...

and here...

International climate policy post-Copenhagen:

Acting now to reinvigorate global action on climate change [COM(2010) 86 final; {SEC(2010) 261}]

1. KEY MESSAGES

The international dimension has always been an essential part of the EU's ambitions on climate change. Europe's core goal is to keep the increase in temperature below 2°C, to prevent the worst impacts of climate change, and this is only possible through a coordinated international effort. This is why the EU has always been a strong supporter of the UN process, and why Copenhagen fell well short of our ambitions. Nevertheless, increasing support for the Copenhagen Accord shows that a majority of countries are determined to press ahead with action on climate change now. The task for the EU is to build on this determination, and to help channel it into action. This Communication sets out a strategy to help maintain the momentum of global efforts to tackle climate change.

The EU has always been at the forefront of concrete action against climate change - it is on track to comply with its 2008-2012 Kyoto commitments, has adopted ambitious targets for 2020, including a commitment to reduce its greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions by 20% by 2020 and to increase this reduction to 30% if the conditions1 are right. We are now ready to transform Europe into the most climate friendly region of the world moving towards a low carbon, resource efficient and climate resilient economy. Realising that, and showing that we are putting the Copenhagen Accord into effect, is a key calling card in the effort to persuade global partners to take up the challenge.

The Europe 2020 Strategy has put more sustainable economic growth at the heart of the vision for the future, creating new jobs and boosting energy security. The Commission will now undertake work to outline a pathway for the EU's transition to a low carbon economy by 2050. It will also strengthen resilience to climate risks and to increase our capacity for disaster prevention and response.

The UN process is essential for a broader global commitment to support action on climate change. Central to this objective is to use the UN process in the run-up to Cancun to integrate the Copenhagen Accord's political guidance into the UN negotiating texts. We also need to address the remaining gaps, and ensure the environmental integrity of an agreement whose bottom line must be to deliver cuts in GHG emissions on the scale required. This implies ensuring a broad participation and a stronger level of ambition from other countries, and addressing possible weaknesses, such as the rules for the accounting of forestry emissions and the handling of surplus emission budgets from the 2008-2012 Kyoto period. This also includes building a robust and transparent emissions and performance accounting framework, mobilising fast-start funding in a coordinated manner and contributing to securing long-term finance for mitigation and adaptation. In addition, the EU should work to advance the development of the international carbon market, by linking compatible national systems, and promoting the orderly transition from the CDM to new sectoral market-based mechanisms.

Our primary objective remains to reach a robust and legally-binding agreement under the UNFCCC. In order to achieve this, we should first focus on the adoption of a balanced set of concrete, action-oriented decisions in Cancun at the end of 2010. This should be as comprehensive as possible, but given remaining differences among Parties, the EU must be ready to continue the work for the adoption of a legally binding agreement in South Africa in 2011. Up to Copenhagen the pressure on expectations had very useful effects leading many major economies to set domestic targets prior to Copenhagen. Now we must consider a strategy that will keep momentum high without jeopardizing the primary objective.

That is why the EU will need to raise the level of its outreach, building confidence that an international deal can be brokered and exploring specific measures to be agreed in Cancun. It needs to focus on building support with different partners.

2. REINVIGORATING INTERNATIONAL CLIMATE NEGOTIATIONS

2.1. Taking stock after Copenhagen

The main outcome of the Copenhagen Climate Change Conference in December 2009 was the agreement among a representative group of 29 Heads of State and Government on the "Copenhagen Accord". The Accord anchors the EU's objective to limit global warming to below 2°C above pre-industrial levels2. It requested developed countries to put forward their emission reduction targets, and invited developing countries to put forward their actions, by 31 January 2010. It also provides the basis for regular monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) of those actions, contains a commitment for significant financing for climate action and a related institutional framework, and gives guidance on tackling issues like reducing emissions from deforestation, technology and adaptation.

The Accord falls well short of the EU's ambition for Copenhagen to reach a robust and effective legally binding agreement, and was only "taken note" of in the conclusions of the Conference. Nevertheless, the more than 100 submissions to date by both developed and developing countries3, many of them including targets or actions, demonstrate a broad and still growing support for the Accord. They demonstrate the clear determination of a majority of countries to step up their actions on climate change now.

Copenhagen also made important progress in the negotiations on a broad range of other issues in the form of draft decisions and negotiating texts4. Together with the Accord, these provide the basis for the next steps, both in the negotiations - where we will now need to integrate the political guidance from the Accord in these UNFCCC negotiating texts - and for the immediate start with the implementation of a number of actions

2.2. A roadmap for the future

The EU should continue to pursue a robust and effective international agreement and a legally-binding agreement under the UNFCCC fundamentally remains its objective. To obtain such agreement, the EU should re-focus its efforts. It should build confidence by responding to the urgent desire for concrete action now as well as seek concrete results from Cancun. This requires a broad approach, with an intensified bilateral outreach.

2.2.1. The UN process

The 2010 Conference is scheduled for December in Cancun, to be followed by one in South Africa at the end of 2011. In the run-up to Cancun, a variety of preparatory meetings will be organised, including by Mexico and Germany.

The April and June meetings in Bonn should set the roadmap for next steps in the negotiations, picking up the negotiations with a focus on integrating the political guidance from the Copenhagen Accord into the various negotiating texts resulting from Copenhagen. The meetings should identify the "gaps" in the current negotiating texts, such as the issue of monitoring, reporting and verification, on which the Accord provides important political guidance. They should also address issues neglected in the Accord, such as the evolution of the international carbon market, reducing emissions from international aviation and maritime transport through the ICAO and IMO, agriculture, and the reduction of hydrofluorocarbons. Most importantly, the Bonn meeting should bring the developed country targets and developing country actions submitted under the Accord into the formal UN negotiating process.

The EU's objective for Cancun should therefore be a comprehensive and balanced set of decisions to anchor the Copenhagen Accord in the UN negotiating process, and to address the gaps. There should also be a formal decision on the listing of developed country targets and the registration of developing country actions, including the methods to account for these. All the decisions should come under an "umbrella" decision to provide the overall political framework. Most importantly, the outcome of Cancun must strike a balance between issues of importance to both developed and to developing countries.

While the EU is ready to adopt a robust and legally binding agreement in Cancun, the substantial differences outstanding mean that we have to recognise the possibility of a more step-by-step approach. Under this scenario, concrete decisions in Cancun would still offer the right basis for a fully fledged legal framework in South Africa in 2011. It is important to anchor the progress made and keep momentum high without jeopardizing the fundamental objective.

2.2.2. Reaching out to third countries

Negotiations in Copenhagen clearly demonstrated that progress in the UN was conditional on the willingness of countries to act. An active outreach programme by the EU will be key to promoting support for the UN process. The objective will be to obtain a better understanding of the positions, concerns, and expectations of our partners on key issues; and to explain clearly what the EU requires of an agreement in terms of its ambition, comprehensiveness, and environmental integrity. It will seek to encourage immediate action to follow up on the

Copenhagen Accord and facilitate convergence on action-oriented decisions to be agreed in Cancun. This should also provide valuable opportunities to intensify bilateral dialogues on domestic climate change developments and for the EU to offer support on domestic action. The Commission will undertake this outreach in close contact with the Council and its Presidency.

The Union and its Member States should continue to pursue the negotiations within the framework of the UN. A stronger role for the Commission will help ensure that the EU speaks with one voice. Building upon the lessons of Copenhagen, we must engage in a discussion on how best to increase the efficiency and leverage of the EU in international negotiations.

In addition, the Commission would encourage and assist the European Parliament to engage fully with parliamentarians from key partner countries.

The outreach activities must happen at all levels and with all the important stakeholders. Bilateral as well as multilateral meetings, including a number of summits and ministerials, are scheduled for 2010. These will be complemented by regional and ad hoc meetings to ensure that partners from all regions of the world are reached, including vulnerable countries, and that the EU increases its understanding of their concerns and ambitions. In informal and formal, existing and new dialogues preparing Cancun and the immediate implementation of the Copenhagen Accord parties must continue to identify key issues and possible compromises in the negotiations. The Commission, supported by EU delegations of the European External Action Service, will engage actively in all these activities. It will do so in close cooperation with incoming Mexican and South African Presidencies of the Conferences in 2010 and 2011.

It is, however, important to underline that there must be a willingness from all Parties to move forward. Without this, the Copenhagen Accord, representing the lowest common denominator, is likely to remain the only agreement possible.

2.2.3. Environmental integrity

An agreement to tackle climate change must deliver the reductions needed to get global GHG emissions on a pathway compatible with the Copenhagen Accord's objective to remain below 2°C. Whilst the Kyoto Protocol remains the central building block of the UN process, its key shortcomings will have to be addressed - its coverage, and the weaknesses it contains.

- The Kyoto Protocol, in its current structure,cannot alone deliver the objective to remain below 2°C. Kyoto only covers 30% of emissions today. The objective is only possible if the US and major emitters from the developing world (including Brazil, China, India, South Korea, Mexico and South Africa, who rank among the world's 15 biggest emitters) will do their share. The EU took a huge responsibility under Kyoto, and the EU is on track to comply with its 2008-2012 commitments. Others must follow suit. Of course, the efforts of developing countries will differ in accordance with their responsibilities and capabilities and may require support.

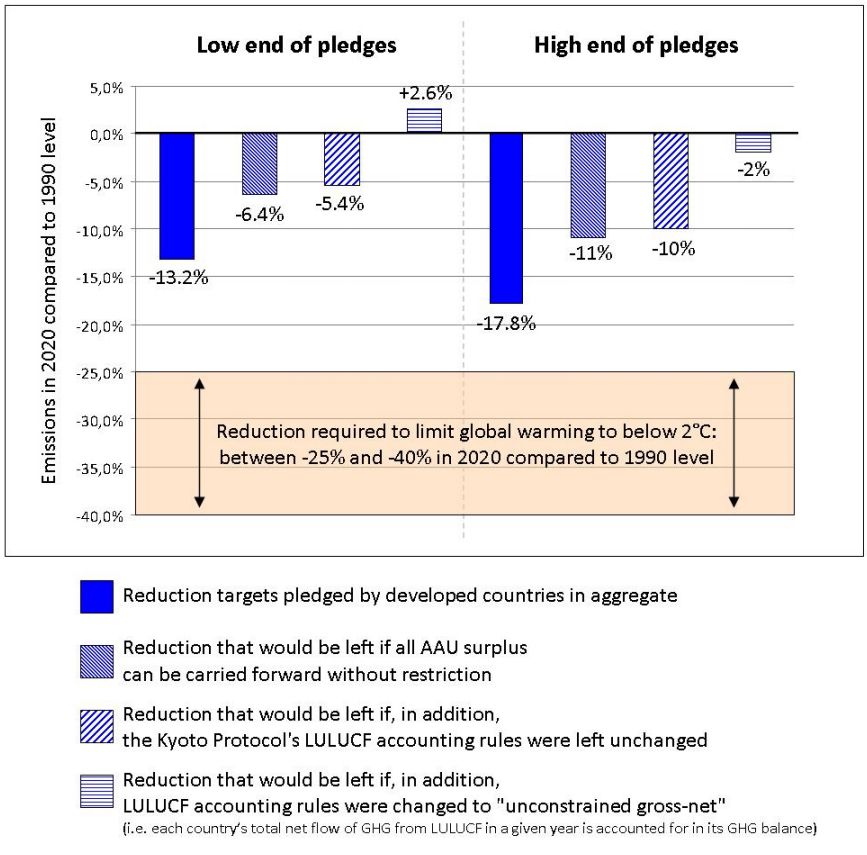

- in addition, serious weaknesses exist in the current Kyoto architecture which risk undermining the environmental integrity of an agreement. Current developed country pledges on the table imply a reduction in their emissions from around 13.2% by 2020 below 1990 level (for the lower end of the pledges) to around 17.8% (for the higher end of the pledges). This is already insufficient to meet the objective to remain below 2°C, for which reductions in the range of 25 to 40% from developed countries are needed. But the two following weaknesses would make the real results even worse:

- Banking of surplus emission budgets (Kyoto Protocol Assigned Amount Units or AAUs) from the Kyoto Protocol's 2008 to 2012 commitment period into future commitment periods: Due to falling emissions, to a large extent resulting from the restructuring of industry in the early 1990s, the 1990 benchmark means that over 10 billion tonnes of GHG emission units will likely remain unused during the 2008 to 2012 commitment period, especially in Russia and the Ukraine. Simply continuing the Kyoto Protocol would mean banking this "surplus", with the effect that headline cuts in emissions would be undermined. Full banking of these units into a second commitment period would cut the ambition of developed country targets by around 6.8% in relation to 1990, i.e. reducing the ambition from 13.2% to 6.4% for the lower end of the pledges, or from 17.8% to 11% for the higher end of the pledges.

- Accounting rules for land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) emissions from developed countries: While the EU has no difficulties in matching these requirements, it is an issue of particular importance for major forestry countries outside the EU and environmentally critical. The current rules under the Kyoto Protocol, if continued, would entail lowering the actual stringency of the current emission reduction pledges and imply that reductions can be claimed without additional actions, which brings no real environmental benefit. In an extreme scenario, the worst-case LULUCF accounting rules would weaken the real level of ambition of developed countries by up to an additional 9% in relation to 1990. This would mean that for the lower end of the pledges we would in fact allow for an increase in developed country emissions of 2.6% above 1990 levels and for the higher end of the pledges we would only see a 2% reduction in relation to 1990.

The European Parliament in its recent post-Copenhagen resolution explicitly pointed at those weaknesses and the need to avoid them undermining the environmental integrity5.

The Commission will assess the merits and drawbacks of alternative legal forms, including of a second commitment period under the Kyoto Protocol.

|

| Adopted on Wednesday 10 February, available through: http://www.europarl.europa.eu. Impact of the Kyoto Protocol's weaknesses (AAU surplus and LULUCF accounting rules) on developed countries' reduction pledges in 2020 |

3 ACTING NOW

3.1. Europe 2020: towards a low carbon and climate resilient economy

The most convincing leadership that the EU can show is concrete and determined action to become the most climate friendly region in the world. This is in the EU's self-interest. The Europe 2020 Strategy has defined sustainable growth – promoting a more resource efficient, greener and more competitive economy – as a priority at the heart of the vision for a resource efficient future for Europe, creating new green jobs and boosting energy efficiency and security.

The Commission will outline a pathway for the EU's transition to a low carbon economy by 2050, to achieve the EU agreed objective to reduce emissions by 80-95%, as part of the developed countries' contribution to reducing global emissions by at least 50% below 1990 levels in 20506. The EU is committed to a 20% emission reduction below 1990 levels in 2020, and to moving to 30% if the conditions are right. Ahead of the June European Council, the Commission will therefore prepare an analysis of what practical policies would be required to implement a 30% reduction. The Commission will thereafter develop an analysis of milestones on the pathway to 2050, including the necessary scenarios of the ambition level for 2030 reflecting the contributions from key emitting sectors, including energy production and consumption, and transport, and set out appropriate strategies for these sectors consistent with the EU 2020 strategy. The goal is to come with intelligent solutions that benefit not only climate change, but also energy security and job creation in our efforts to decarbonise the economy.

Such action will need to have a strong focus on policies to accelerate innovation and early deployment of new technologies and infrastructure, creating a competitive edge for European companies in key sectors of the future (including energy efficiency, green cars, smart grids, carbon capture and storage (CCS), renewable energy). It will benefit from approaches that maintain and promote strong and resilient ecosystems.

The Commission will also set out, in the light of the outcome of Copenhagen and in line with the agreed deadline in the ETS Directive, its analysis on the situation of energy intensive industries in the event of carbon leakage.

3.2. Implementing the Copenhagen Accord

3.2.1. Delivering on remaining below 2°C: targets and actions

The outcome of Copenhagen, and the broad support for the Copenhagen Accord, demonstrates the political will from the majority of countries to start action now. By far the biggest achievement of Copenhagen is the fact that, by the end of January 2010, developed and developing countries representing more than 80% of global GHG emissions have put forward their GHG reduction targets and actions7.

Even though this underlines a real willingness to take action, the overall ambition level of targets and actions put forward so far is hard to assess. Optimistic assessments of the economy-wide targets and mitigation actions indicate that a pathway towards limiting the global temperature increase to no more than 2ºC is still feasible, but more pessimistic assessments indicate that this chance is disappearing fast.

Even if the weaknesses described above were closed, the targets proposed by developed countries, even the higher, conditional pledges, do not come close to the 25-40% reductions by 2020 that are required, based on the IPCC's assessment, to remain below a 2°C temperature increase. In addition, so far only the EU has adopted the legislation required to guarantee the delivery of its 2020 reduction target. In other developed countries, legislation is still at the discussion stage only.

The fact that developing countries have put forward their actions is an unprecedented step forward. However, there remains much uncertainty about the real action to be taken, its timetable, and how it might relate to the established comparable benchmark of reductions since 1990.

With a broad range of pledges for targets and actions on the table, the negotiations should now focus on a clarification of those pledges, a discussion of their overall level of ambition and how this ambition could be further strengthened. This should be the first priority of the UN process.

3.2.2. Building a robust and transparent emissions and performance accounting framework

Among the most difficult negotiations in Copenhagen were those on monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV). Transparency is key to ensure mutual trust and demonstrate the effectiveness and adequacy of targets and actions. The Climate Change Convention and its Kyoto Protocol provide basic standards of MRV, through national communications and inventories. The Copenhagen Accord requires the strengthening of this system. This must be one of the priorities in the work to anchor the compromises in the Copenhagen Accord in the UN process.

But transparency must not be limited to the reporting of emissions alone. What matters in the end is the performance of countries in the implementation of their targets or actions. As already explained above, the rules for the accounting of emissions have a huge impact on the real scale of action. Robust, transparent and predictable accounting rules that make it possible to assess countries' performance properly are essential.

In the meantime, the Commission proposes to embark on regional capacity building programmes for interested developing countries to develop their monitoring, reporting and verification capabilities, including emission inventories.

3.2.3. Mobilising fast-start funding in a coordinated manner

The Copenhagen Accord provides for fast-start support to developing countries approaching US$ 30 billion for the period 2010-2012, with balanced allocation between mitigation and adaptation. The December European Council set the contribution of the EU and its Member States at € 2.4 billion yearly for the period 2010-2012. The swift implementation of this EU commitment is essential to both the EU's credibility and the urgent need to enhance the capacity of many developing countries to design and implement effective climate policies in the areas of adaptation, mitigation and technology cooperation.

The EU must engage with other donors and recipients to ensure coordinated implementation of the fast start funding agreed in Copenhagen.

Fast-start actions could cover, for example, capacity building for integrating adaptation into development and poverty reduction strategies, as well as the implementation of pilot and urgent adaptation actions as identified in national action plans; capacity building in the area of mitigation, i.e. low-emission development strategies, nationally appropriate mitigation actions, and emissions monitoring, reporting and verification; capacity-building and pilot projects for sector-wide carbon market mechanisms; readiness and pilot projects for reducing emissions from developing country deforestation, and capacity building and pilot projects in technology cooperation. Fast-start funding must be well targeted to different regions of the world in order to effectively build climate policy capacity, respond to developing countries' needs and specific proposals and deliver environmental results where it is most needed8.

In order to be effective and avoid delay of ambitious action, fast-start funding must build on and take account of existing initiatives. A substantial part of the EU fast-start funding will be implemented through existing initiatives9, bilateral channels, in particular by Member States' own development cooperation programmes, or through international institutions. EU initiatives can build on existing initiatives or target new needs like MRV and low-emission development strategies. The Commission and individual Member States could take the lead in specific countries or regions and for specific themes, depending on their funding priorities and

on the priorities of their respective partner countries.

The EU will need to act and report on its actions in a consistent and efficient manner, avoiding duplication and maximising synergies. Coordination of the EU's efforts will be critical. The Commission is ready to take on a facilitating and coordinating role in the implementation of the EU's fast-start funding commitment, and proposes to:

(1) work with the ECOFIN Council, supported by the relevant Council formations, to coordinate and monitor EU fast-start funding efforts;

(2) establish a joint EU regional capacity building programme (e.g. for low emission development strategies and adaptation strategies) to pool and channel EU funding, complementing existing EU financial programmes. This could directly involve countries interested in capacity building, e.g. through 'twinning' arrangements;

(3) ensure transparency through the provision of a bi-annual progress report on the implementation of the EU's fast-start funding commitment, with a first report in time for the Bonn UNFCCC session in June 2010.

3.2.4. Securing long-term finance

In the Copenhagen Accord, the EU and other developed countries committed to jointly mobilise US$ 100 billion (€ 73 bn) per year by 2020 for mitigation and adaptation actions in developing countries. This finance could come from a wide range of sources:

– The international carbon market, which, if designed properly, will create an increasing financial flow to developing countries and could deliver up to € 38 billion per year by 2020. The EU ETS is already providing significant flows to developing countries via its support of the CDM, and EU legislation provides for additional flows from 2013. In addition, Member States have committed to use a part of their auction revenues under the EU ETS for these purposes from 2013;

– International aviation and maritime transport, preferably through global instruments10, which can provide an important source of innovative financing, building on the existing commitment under the EU ETS for all aviation auction revenues to be used for climate change measures;

– International public funding in the range of € 22 to 50 billion per year by 2020. The EU should contribute a fair share. For the period after 2012, the EU would continue to make a single, global EU offer11.

The future UN High-Level Panel on Finance and the High-Level Advisory Group on Climate Change Financing should explore how these sources can be effectively used for financing future climate actions, with public finance focusing on areas that cannot be adequatelyfinanced by the private sector or used to leverage private investments. The Copenhagen Green Climate Fund also needs a well-defined mandate to add value to existing initiatives.

Governance of the future international financial architecture should be transparent, allow for effective monitoring, and should respect agreed principles for aid effectiveness. A fully transparent reporting system is needed, using a comprehensive set of statistics which build on the OECD-DAC system. This will ensure climate action happens in synergy with poverty reduction efforts and efforts towards the Millennium Development Goals.

The international dimension of long-term finance is only a part of the picture. In contacts with developing countries, especially the economically more advanced, it must be clear that they will also contribute to the overall effort, including by engaging in meaningful mitigation actions and transparency on implementation.

3.3. Advancing the international carbon market

A well-functioning carbon market is essential for driving low-carbon investments and achieving global mitigation objectives in a cost-efficient manner. It can also generate important financial flows to developing countries. An international carbon market should be built by linking compatible domestic cap-and-trade systems. The goal is to develop an OECD- wide market by 2015 and an even broader market by 2020, so this should be part of the outreach to the US, Japan and Australia, in view of the progress they have achieved so far. The EU has proposed new sectoral carbon market mechanisms as an interim step towards the development of (multi-sectoral) cap and trade systems, in particular in the more advanced developing countries. These mechanisms can provide a more comprehensive price signal and generate credits on a greater scale. They can also provide a way to capture mitigation contributions by developing countries by crediting against ambitious emission thresholds set below projected emissions to ensure a net mitigation benefit.

In addition, the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) will continue post-2012, but it must be reformed to improve its environmental integrity, effectiveness, efficiency, and governance. Over time it should increasingly focus on least developed countries. To ensure a coherent transition from project-based to sector-wide mechanisms, the EU should seek common ground with the US and other countries implementing cap-and-trade systems and generating demand for credits in a coordinated manner.

A major goal for Cancun should be to anchor the improved and new carbon market mechanisms as means to reach ambitious mitigation objectives and generate financial flows to developing countries. In addition, it should provide a basis for the creation of new sector-wide mechanisms. However, over the last years negotiations on market-based mechanisms have been met with severe criticism from a number of developing countries, putting into question whether this can be done under the auspices of the UNFCCC.

The EU should therefore use the provisions of the current EU ETS legislation12 to incentivise the development of sectoral carbon market mechanisms and to promote the reform of the CDM. To this end, the Commission will:

- work together with interested developed and developing countries to develop sectoral mechanisms, whose credits could then be recognized for use in the EU ETS, in the emerging OECD-wide market and under the EU's Effort Sharing Decision containing Member State reduction commitments; and

- dependent on progress in the development of sector-wide mechanisms, develop and propose strict measures for improving the quality requirements for credits from project-based mechanisms.

4. CONCLUSION

This communication takes stock of some lessons after the Copenhagen Conference, which fell short of initial ambitions, but which nevertheless show the substantial and widespread support to step-up efforts to address climate change. The Communication also maps out the steps going forward in the near- and medium-terms, and crucially signals the Commission's determination to continue its efforts to ensure adequate action is taken globally in keeping with the seriousness of the global challenge confronting us.

The European Council of 10-11 December 2009 concluded that as part of a global and comprehensive agreement for the period beyond 2012, the EU reiterates its conditional offer to move to a 30% reduction by 2020 compared to 1990 levels, provided that other developed countries commit themselves to comparable emission reductions and that developing countries contribute adequately according to their responsibilities and respective capabilities.

(2) The Accord even calls for consideration of strengthening the long-term goal, including in relation to temperature rises of 1.5°C.

(3) An overview of submissions thus far can be found in the staff working paper accompanying this Communication and on http://www.unfccc.int.

(4) The various draft decisions and negotiating texts are contained in the report of COP-16 and CMP-6, available through http://www.unfccc.int.

(5) Adopted on Wednesday 10 February, available through: http://www.europarl.europa.eu

(6) European Council of 29-30 October 2009 concluded that: "The European Council calls upon all Parties to embrace the 2°C objective and to agree to global emission reductions of at least 50%, and aggregate developed country emission reductions of at least 80-95%, as part of such global emission reductions, by 2050 compared to 1990 levels; such objectives should provide both the aspiration and the yardstick to establish mid-term goals, subject to regular scientific review. It supports an EU objective, in the context of necessary reductions according to the IPCC by developed countries as a group, to reduce emissions by 80-95% by 2050 compared to 1990 levels."

(7) An overview of targets and actions put forward thus far is provided in the staff working paper accompanying this Communication

(8) As per the Copenhagen Accord, funding for adaptation will be prioritised for the most vulnerable developing countries, such as the LDCs, SIDS and Africa.

(9) Including through the Global Climate Change Alliance (GCCA)

(10) ECOFIN Council, 9 June 2009 and COM(2009) 475.

(11) Cf. COM(2009) 475.

(12) Articles 11a(5) and 11a(9) of the EU ETS Directive 2009/29/EC and Article 5(2) of Decision No 406/2009/EC.

---------------