For mill towns, China beckons

-----------------

Pine trunks rumble down conveyors and sawdust clouds the air. The noise inside the sawmill nearly deafens, but in this remote town of 3,500 people, some 700 kilometres north of Vancouver, there are few sounds as welcome as the buzz and clatter of a mill back at work.

People in Mackenzie have worked in sawmills since the town was carved out of the wilderness back in 1966. For decades, most of the lumber they produced headed straight to the United States – until the U.S. housing bubble burst in 2007 and demand collapsed. One after the other, the local mills closed. Mackenzie itself appeared to be on a conveyor belt to extinction.

But salvation has emerged from a faraway source. As a result of growing demand from across the Pacific, Canfor Corp. reopened its Mackenzie mill last year, part of a massive bet by British Columbia’s forestry industry on the potential of the Chinese market.

The province’s foresters are gambling that new demand generated by China’s rapidly expanding economy can wrench towns like Mackenzie out of the worst slump in their history. “The volume China could consume is far beyond our capacity to supply,” says Pat Bell, B.C.’s forests minister. “It would be enormous.”

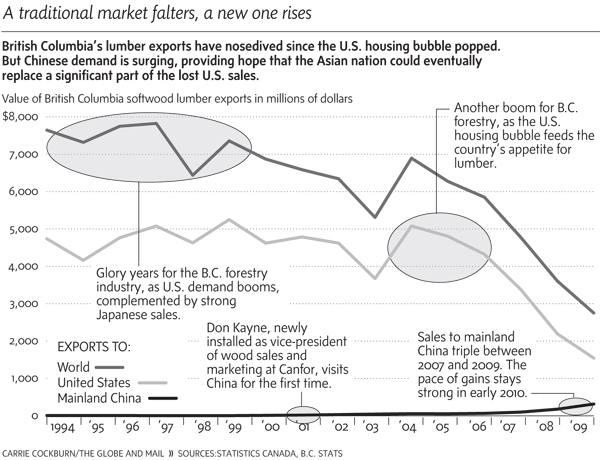

Annual exports of B.C. timber to mainland China tripled over the past two years, reaching more than $300-million in 2009 on a volume of 2.5 million cubic metres. In the first four months of this year, exports hit $132-million – 60 per cent higher than a year earlier and more than was sold during all of 2007.

Mr. Bell predicts that China could soon be buying 10 million cubic metres of B.C. lumber a year. A breakthrough of that size in China would radically reduce the province’s dependence on the depressed U.S. market and give the forest industry a second cornerstone for future growth.

Success, though, is far from assured. To win in China, Canada’s foresters must convince a nation of 1.3 billion people to begin using wood, rather than concrete and steel, for construction.

Canadians must try to accomplish that feat as concerns grow over China’s housing bubble. After several years of rapidly rising prices and speculative building, the supply of apartments in many eastern Chinese cities appears to vastly exceed demand. According to a recent report from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, vacancy rates of more than 30 per cent are common.

As the Chinese government tries to deflate its real estate bubble, the pace of building is slowing. GaveKal Dragonomics, a Beijing research firm, predicts large declines in construction through the rest of this year. For Canadian wood producers, it’s a cruel twist: Having been hit hard by the collapse of the U.S. housing bubble, they now face a similar problem in their new market.

But Canada’s foresters are forging ahead. They know that the long-term potential of China is enormous. For Canadian forestry companies, China is not a quick profit grab. It is an attempt to ensure the viability of the industry – and places like Mackenzie – for a generation.

|

| ‘Canfor College’ in Shanghai, which the company established to train young people from rural cities to be carpenters. |

A carpenter school

Don Kayne, Canfor’s vice-president of wood sales and marketing, has been seeding the Chinese market for nearly a decade.

On his first visit to the country in 2001, B.C.’s wood exports to mainland China were worth just 0.4 per cent of the province’s sales to the U.S., and China’s potential as a lumber market was next to invisible. The country had burned through forests of its own wood to fuel steel factories during Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward in the 1960s. A generation had grown up with no experience of wooden housing.

Mr. Kayne arrived in a China where carpenters were unknown, and where wood was viewed as a flimsy, flammable material fit only for peasants.

His most immediate problem was $70,000 of unsold lumber sitting in a warehouse in Beijing and a local agent who couldn’t give it away. Mr. Kayne’s bosses were growing skeptical. “I was getting heat, ‘We can’t keep going like this.’ ”

Then, through a mutual acquaintance, he met Mayco Lou, a Taiwan-born, North American-educated businessman who had started a small lumber importing business in Shanghai. “I told Mayco the situation and said, ‘If you can sell this, I’ll give you a shot at being our agent,’ ” Mr. Kayne says. “So he went away and a week later it was sold, gone.”

Mr. Lou hustled, working with his contacts in the region and a young sales team. He moved the lumber to Shanghai from Beijing and dispatched his hungry work force on bicycles, motorbikes, buses and trains to peddle the product wherever they could.

Buoyed by the sale, Canfor went to work. It established “Canfor College” in Shanghai, which trained 250 young people from rural cities to be carpenters.

Canfor soon turned over the effort to Canada Wood, a federal-provincial marketing body, which opened an office in Shanghai in 2002 and continues to train local carpenters. Canada Wood worked closely with B.C.’s Forest Innovation Investment Ltd., a provincially owned corporation that aims to develop new uses for B.C. lumber.

In 2005, Canfor bought Mr. Lou’s business. “It showed people in the country we were serious,” Mr. Kayne says.

To demonstrate his own commitment to China, Mr. Kayne has visited the country about 25 times and is working to improve his Mandarin – vital steps in a country where building personal relationships is crucial. He says foreigners must demonstrate to Chinese locals that they are in the country for the long haul, not just to extract a fast buck.

Proving that level of dedication can require strong nerves. In June, 2009, Mr. Kayne and several other Canadian forestry executives climbed on a bus to the rural counties that had been at the epicentre of the devastating Sichuan earthquake of 2008. In a joint humanitarian and marketing effort, the Canadian government and B.C. foresters had worked together to build wooden homes and schools, designed to resist earthquakes better than the concrete structures common in China.

“You’re up on the mountains going through, there’s no guardrail, it’s just a straight drop off,” Mr. Kayne says. “This guy came sailing around, a bus going the other way, there’s no room, I’ll never forget it. He was right there” – Mr. Kayne motions with his hands – “and I don’t know to this day how he missed us. I thought – we all did – we were done.”

The experience didn’t dissuade Mr. Kayne. He notes that last year the value of B.C.’s wood sales to China surpassed 20 per cent of the province’s sales to the U.S., a huge advance from when he first visited the country.

Even if the country’s property bubble bursts, he believes the market is so large, and Canfor and Canadian efforts so relatively small at the moment, that there will be plenty of room for growth. “China’s going to be good,” he says. “I can’t see how it can’t be. I just can’t.”

Targeting housing

While China may eventually live up to Mr. Kayne’s hopes, even optimists acknowledge that right now the hype obscures the extended slog ahead. “The story in China’s being oversold,” says Russ Taylor, president of consultants Wood Markets International in Vancouver. “It [sounds like] a great story: All you hear is China is short of lumber and B.C. is the solution.”

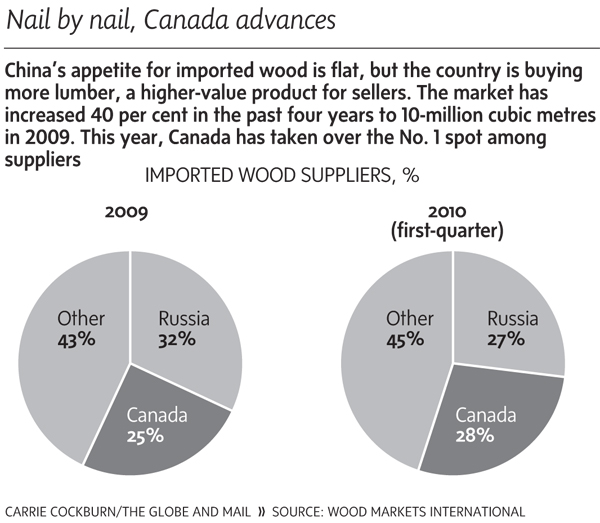

In fact, China’s overall demand for wood of all kinds has been flat over the past few years. Much of its appetite is for raw logs that go into the country’s factories to produce other goods. Russia is a fierce competitor for those sales, as are China’s own wood producers, who are expanding their plantations.

Canada’s forest industry believes its future lies in selling more valuable lumber for housing. The industry’s initial idea, a decade ago, was to promote the use of lumber for building single family homes, but the foray sputtered when it met the financial realities of Chinese society, where only the rich live in such houses.

Since then, Canada Wood, the government marketing body, and Forest Innovation have ceaselessly worked China’s bureaucracy, opening up new niches, such as using wood in trusses to fix the flat, leaking roofs of old concrete apartment buildings. Meanwhile, the industry has relentlessly promoted wood’s energy efficiency and the ability of wooden structures to withstand earthquakes. “We’re still teaching the Chinese to hammer and saw,” Mr. Taylor says. “But if one of these ideas takes off, five or 10 years from now, we might never look back.”

The great new hope is that China may begin using wood to construct apartment buildings. Last year, Canada Wood and Forest Innovation won approval for a new wood-building code in Shanghai for six-storey apartment buildings. This year, three of the biggest B.C. forest producers – West Fraser Timber Co. Ltd., Canfor and Tolko Industries Ltd. – are coming together with smaller suppliers to construct a demonstration building in Beijing. The consortium plans to showcase it to the top-tier of China’s government, led by Qiu Baoxing, vice-minister of housing and urban-rural development.

The B.C. and Canadian governments are chipping in about $5-million for the demonstration project – an expenditure that elicited a few jeers from critics in B.C. who can’t see why Canadian taxpayers should partly fund something that China can easily afford itself. To Mr. Bell, the B.C. forests minister, it’s a small ante with an enormous potential payoff.

The minister, whose home base lies in Prince George, B.C., close to ravaged mill towns like Mackenzie, became an immediate evangelist for the potential of the Chinese market after his first visit to the country in 2008: “What struck me was how rapidly things were evolving and how entrepreneurial China was. I realized the U.S. was a ways off from recovery – and I knew we needed a new market.”

Some people questioned Mr. Bell’s enthusiastic projections for Chinese sales, but he has achieved results. He led a group of forest industry CEOs on a trade mission to China last November. Through a connection forged by a friendship between a Canada Wood staffer in Beijing and a person in Mr. Qiu’s office, there was a short, but key, half-hour meeting with Mr. Qiu. At the behest of the senior housing minister, the Canadians were back in March for a green-building conference. At a dinner, Mr. Bell was surprised where he was seated.

“I was directly beside Mr. Qiu,” Mr. Bell says. “You’d be hard-pressed to get a federal minister with a Chinese minister at that level. It’s all about the value of relationships.”

Mr. Bell believes it’s crucial for B.C.’s forest industry CEOs to sell themselves to China as a unified group, rather than as a loose cluster of individual firms. “The status quo had always been big companies would go and develop a market on their own,” he says. “In China, it’s collaborative. We’re seen as a single face. It’s what’s helped us grow in China so quickly.”

Small town hope

The rapid growth in Chinese sales is sparking renewal in small mill towns, such as Quesnel, 300 kilometres south of Mackenzie. Canfor restarted a shuttered mill there in June, solely to supply Chinese customers. For Quesnel, the reopening means a much-needed 155 jobs.

In Mackenzie, where a second shift was added earlier this year, Canfor’s mill employs 140 people. Several hundred more jobs are expected when two other Mackenzie mills reopen later this year.

Many forces came together to allow Canfor to revive its Mackenzie operation. Workers agreed to pay cuts of almost 30 per cent (although incentives will reward them if the mill does well). The town provided a generous dose of support, cutting property taxes by 25 per cent for three years. But underlying it all was the prospect of growing demand from China.

“It’s filled a huge void for us,” says Lionel Chabot, general manager of the Mackenzie mill.

After coming close to death a couple of years ago, Mackenzie is in a slow convalescence.

“I saw a lot of friends leave, I saw a lot of friends struggle,” says Amber Hancock, a computer consultant and president of the local chamber of commerce in 2008 and 2009.

“But I’m confident. We’ll be stronger – not the same and not as big, but stronger. You really see it, everywhere, from Facebook to people talking in the mall.”

The Japanese alternative

Years before they began their big push into China, B.C. foresters already had a vibrant second market in Asia. B.C. producers did a brisk trade with Japan, which had a long history of building with wood and a taste for expensive high-grade lumber.

From the late 1980s, when annual exports to Japan were $1-billion, B.C.’s sales to the Asian nation exploded, reaching a high of $2.5-billion in 1995, when exports to Japan were worth 60 per cent of what B.C. sent to the U.S.

Then the 1997-98 Asian crisis struck and Japanese sales plunged. Although there was some recovery, B.C.’s forestry industry turned its attention to the booming U.S. market, abandoning customers in Japan … which sent sales into a precipitous spiral.

Last year, sales of $532-million were off almost 80 per cent from the peak.

---------------